click to enlarge The Emancipation Proclamation consists of two executive orders issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War. The first one, issued September 22, 1862, declared the freedom of all slaves in any state of the Confederate States of America that did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. The second order, issued January 1, 1863, named the specific states where it applied. The Emancipation Proclamation was widely attacked at the time as freeing only the slaves over which the Union had no power, but in practice, it committed the Union to ending slavery, which was controversial in the North. It was not a law passed by Congress, but a presidential order empowered, as Lincoln wrote, by his position as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" under Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution. The proclamation did not free any slaves of the border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware, and West Virginia), or any southern state (or part of a state) already under Union control. It first directly affected only those slaves that had already escaped to the Union side, but as the Union armies conquered the Confederacy, thousands of slaves were freed each day until nearly all (approximately 4 million, according to the 1860 census) were freed by July of 1865. After the war there was concern that the proclamation, as a war measure, had not made the elimination of slavery permanent. Several former slave states had prohibited slavery; however, some slavery continued to exist until the entire institution was finally wiped out by the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment on December 18, 1865. An application of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 would have required the return of fugitive slaves to their owners. Initially this did not occur because some Union generals declared slaves in re-occupied areas were contraband of war. This was controversial because it could imply some recognition of the Confederacy as a separate nation under international law, a notion that Lincoln steadfastly denied; as a result, he never promoted the contraband designation. Some generals also declared the slaves to be free and were replaced when they refused to rescind such declarations. On March 13, 1862, Lincoln forbade all Union Army officers from returning fugitive slaves. On April 10, 1862, Congress declared that the federal government would compensate slave owners who freed their slaves. All slaves in the District of Columbia were freed in this way on April 16, 1862. On June 19, 1862, Congress prohibited slavery in United States territories, thus opposing the 1857 opinion of the Supreme Court of the United States in the Dred Scott Case that Congress was powerless to regulate slavery in U.S. territories. In January 1862, Thaddeus Stevens, the Republican leader in the House, called for total war against the rebellion, arguing that emancipation would ruin the rebel economy. In July 1862, Congress passed and Lincoln signed the "Second Confiscation Act." It liberated the slaves held by "rebels". It provided:

Abolitionists had long been urging Lincoln to free all slaves. A mass rally in Chicago on September 7, 1862, demanded an immediate and universal emancipation of slaves. A delegation headed by William W. Patton met the President at the White House on September 13. Lincoln had declared in peacetime that he had no constitutional authority to free the slaves. Even used as a war power, emancipation was a risky political act. Public opinion as a whole was against it. There would be strong opposition among Copperhead Democrats and an uncertain reaction from loyal border states. Lincoln first discussed the proclamation with his cabinet in July 1862, but he felt that he needed a Union victory on the battlefield so it would not look like an act of desperation. The Battle of Antietam, in which Union troops turned back a Confederate invasion of Maryland, gave him the opportunity to issue a preliminary proclamation on September 22, 1862. The final proclamation was then issued in January of the following year, 100 days later. Although implicitly granted authority by Congress, Lincoln used his powers as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, "as a necessary war measure" as the basis of the proclamation, rather than the equivalent of a statute enacted by Congress or a constitutional amendment. The Emancipation Proclamation did not immediately free many slaves. Secretary of State William H. Seward commented, "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free." Had any seceding state rejoined the Union before January 1, 1863, it could have kept slavery, at least temporarily. The Proclamation only gave Lincoln the legal basis to free the slaves in the areas of the South that were still in rebellion. Thus, it initially freed only some slaves already behind Union lines. However, it also took effect as the Union armies advanced into the Confederacy. The Emancipation Proclamation also allowed for the enrollment of freed slaves into the United States military. Nearly 200,000 blacks did join, most of them ex-slaves. This gave the North an additional manpower resource that the Confederacy would not emulate until the final months before its defeat. Though the counties of Virginia that were soon to form West Virginia were specifically exempted from the Proclamation, a condition of its admittance to the Union was that the new state's constitution at least gradually abolish slavery. Slaves in the border states of Maryland, Missouri were also emancipated by separate state action before the Civil War ended. In early 1865, Tennessee adopted an amendment to its constitution prohibiting slavery. Slaves in Kentucky and Delaware were not emancipated until the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified. The Proclamation was issued in two parts. The first part, issued on September 22, 1862, was a preliminary announcement outlining the intent of the second part, which officially went into effect 100 days later on January 1, 1863, during the second year of the Civil War. It was Abraham Lincoln's declaration that all slaves would be permanently freed in all areas of the Confederacy that had not already returned to federal control by January 1863. The ten affected states were individually named in the second part. Not included were the Union slave states of Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and Kentucky. Also not named was the state of Tennessee, which Union armies already controlled. Specific exemptions were stated for areas also under Union control on January 1, 1863, namely 48 counties that would soon become West Virginia, seven other named counties of Virginia, New Orleans and 13 named parishes nearby. Booker T. Washington, as a boy of 9, remembered the day in early 1865:

The Emancipation took place without violence by masters or ex-slaves. The proclamation represented a shift in the war objectives of the North—reuniting the nation would no longer become the sole outcome. It represented a major step toward the ultimate abolition of slavery in the United States and a "new birth of freedom". Some slaves were freed immediately by the proclamation. Runaway slaves who had escaped to Union lines were being held by the Union Army as "contraband of war" in contraband camps; when the proclamation took effect, they were told at midnight that they were free to leave. The Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia had been occupied by the Union Navy earlier in the war. The whites had fled to the mainland while the blacks stayed, and an early program of Reconstruction was set up for them. Naval officers read the proclamation to them and told them they were free. In the military, the reaction to this proclamation varied widely, with some units nearly ready to mutiny in protest, and desertions were attributed to it. Other units were inspired with the adoption of a cause that seemed to them to ennoble their efforts, such that at least one unit took up the motto "For Union and Liberty". Slaves had been part of the "engine of war" for the Confederacy. They produced and prepared food; sewed uniforms; repaired railways; worked on farms and in factories, shipping yards, and mines; built fortifications; and served as hospital workers and common laborers. News of the Proclamation spread rapidly by word of mouth, arousing hopes of freedom, creating general confusion, and encouraging many to escape. The Proclamation was immediately denounced by Copperhead Democrats who opposed the war and tolerated both secession and slavery. It became a campaign issue in the 1862 elections, in which the Democrats gained 28 seats in the House as well as the governorship of New York. Many War Democrats who had supported Lincoln's goal of saving the Union, balked at supporting emancipation. Lincoln's Gettysburg Address in November of 1863 made indirect reference to the Proclamation and the ending of slavery as a war goal with the phrase "new birth of freedom". The Proclamation solidified Lincoln's support among the rapidly growing abolitionist element of the Republican Party, and ensured they would not block his re-nomination in 1864. Abroad, as Lincoln hoped, the Proclamation turned foreign popular opinion in favor of the Union for its new commitment to end slavery. That shift ended any hope the Confederacy might have had of gaining official recognition, particularly from the United Kingdom. If Britain or France, both of which had abolished slavery, continued to consider supporting the Confederacy, it would seem as though they were supporting slavery. Prior to Lincoln's decree, Britain's actions had favored the Confederacy, especially in its construction of warships such as the CSS Alabama and CSS Florida. As Henry Adams noted, "The Emancipation Proclamation has done more for us than all our former victories and all our diplomacy." Giuseppe Garibaldi hailed Lincoln as "the heir of the aspirations of John Brown". Alan Van Dyke, a representative for workers from Manchester, England, wrote to Lincoln saying, "We joyfully honor you for many decisive steps toward practically exemplifying your belief in the words of your great founders: 'All men are created free and equal.'" This eased tensions with Europe that had been caused by the North's determination to defeat the South at all costs, even if it meant upsetting Europe, as in the Trent Affair. Near the end of the war, abolitionists were concerned that the Emancipation Proclamation would be construed solely as a war act and thus no longer apply once fighting ended. They were also increasingly anxious to secure the freedom of all slaves, not just those freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. Thus pressed, Lincoln staked a large part of his 1864 presidential campaign on a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery uniformly throughout the United States. Lincoln's campaign was bolstered by separate votes in both Maryland and Missouri to abolish slavery in those states. Maryland's new constitution abolishing slavery took effect in November 1864. Slavery in Missouri was ended by executive proclamation of its governor, Thomas C. Fletcher, on January 11, 1865. Winning re-election, Lincoln pressed the lame duck 38th Congress to pass the proposed amendment immediately rather than wait for the incoming 39th Congress to convene. In January 1865, Congress sent to the state legislatures for ratification what became the Thirteenth Amendment, banning slavery in all U.S. states and territories. The amendment was ratified by the legislatures of enough states by December 6, 1865. There were about 40,000 slaves in Kentucky and 1,000 in Delaware who were then also liberated. The proclamation was lauded in the years after Lincoln's death. The anniversary of its issue was celebrated as a black holiday for more than 50 years; the holiday of Juneteenth was created to honor it. In 1913, the fiftieth anniversary of the Proclamation, there were particularly large celebrations. As the years went on and American life continued to be deeply unfair towards blacks, cynicism towards Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation increased. Some 20th century black intellectuals, including W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin and Julius Lester, have described the proclamation as essentially worthless. Perhaps the strongest attack was Lerone Bennett's Forced into Glory: Abraham Lincoln's White Dream, which claimed that Lincoln was a white supremacist who issued the Emancipation Proclamation in lieu of the real racial reforms that radical abolitionists were pushing for. In his Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, Allen C. Guelzo notes the professional historians' lack of substantial respect for the document, since it has been the subject of few major scholarly studies. He argues that Lincoln was America's "last Enlightenment politician" and as such was dedicated to removing slavery strictly within the bounds of law. The Emancipation Proclamation was on display at the William J. Clinton Presidential Center and Park in Little Rock, Arkansas, from September 22-25, 2007 as part of the Little Rock Central High School 50th anniversary of integration. Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer SPECIAL REQUEST FOR TCD FANS: The San Francisco Chronicle is pondering the addition of new cartoons for their paper - a process that seems to be initiated by Darren Bell, creator of Candorville (one of my daily reads - highly recommended). You can read the Chronicle article here and please add your thoughts to the comments if you wish. If anything, put in a good word for Darren and Candorville. I am submitting Town Called Dobson to the paper for their consideration. They seem to have given great weight to receiving 200 messages considering Candorville. I am asking TCD fans to try to surpass that amount. (I get more than that many hate mails a day, surely fans can do better?) This is not a race between Darren and I, it is a hope that more progressive strips can be represented in the printed press of America. So if you read the San Francisco Chronicle or live in the Bay Area (Google Analytics tell me there are a lot of you), please send your kind comments (or naked, straining outrage) to David Wiegand at his published addresses below. If you are a subscriber, cut out your mailing label and staple it to a TCD strip and include it in your letter. candorcomment@sfchronicle.com or David Wiegand Executive Datebook Editor The San Francisco Chronicle 901 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 |

Friday, May 2, 2008

Black History: Emancipation

Posted by

Storm Bear

at

7:23 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cartoons, civil war, comics, emancipation proclamation, Feminism, webcomics

The Shadow Knows

Posted by

Anonymous

at

5:03 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Barrack Obama, Langston Hughes, The Reverend Wright

Thursday, May 1, 2008

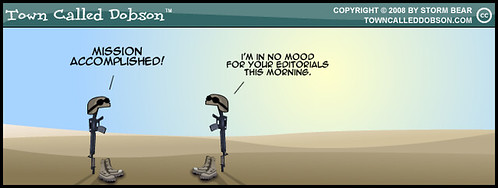

My View of Mission Accomplished

click to enlarge I am submitting Town Called Dobson to the paper for their consideration. They seem to have given great weight to receiving 200 messages considering Candorville. I am asking TCD fans to try to surpass that amount. (I get more than that many hate mails a day, surely fans can do better?) This is not a race between Darren and I, it is a hope that more progressive strips can be represented in the printed press of America. So if you read the San Francisco Chronicle or live in the Bay Area (Google Analytics tell me there are a lot of you), please send your kind comments (or naked, straining outrage) to David Wiegand at his published addresses below. If you are a subscriber, cut out your mailing label and staple it to a TCD strip and include it in your letter. candorcomment@sfchronicle.com or David Wiegand Executive Datebook Editor The San Francisco Chronicle 901 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 |

Posted by

Storm Bear

at

8:01 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: afghanistan, cartoons, comics, humor, iraq, missioin accomplished, politics, war, webcomics

The Operation Was A Success, But The Airline Died

Northwest CEO to get $22.1 Million after merger Northwest Airlines CEO Doug Steenland would get an exit payout worth an estimated $21.1 million should he leave following a merger with Delta Air Lines, according to a regulatory filing Tuesday. Delta and Northwest announced a merger deal on April 14 that, if approved by the Justice Department, would see Delta CEO Richard Anderson lead the combined company. Steenland would leave management and become a board member. His exit package includes $3.3 million in severance, $4.5 million in accrued pension, and $8 million in restricted stock that would vest upon his departure. Steenland's 2007 compensation totaled $8.4 million after adjusting for a decline in the value of restricted stock granted early in the year. In the bizarro world of today's financial market, nothing succeeds like failure. You're doing a heckuva job, Doughie! |

Posted by

Anonymous

at

4:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Another incompetent CEO rewarded with a pay raise, Delta, Northwest

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Black History: Southerners Contemplate Manual Labor

click to enlarge Union forces in the East attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's Overland Campaign") of the Eastern campaign. Grant's battles of attrition at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor resulted in heavy Union losses, but forced Lee's Confederates to fall back again and again. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 65,000 casualties in seven weeks), kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. He pinned down the Confederate army in the Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months. Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Sheridan defeated Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the Shenandoah Valley, a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia. Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood along the way. The fall of Atlanta, on September 2, 1864, was a significant factor in the reelection of Lincoln as president. Hood left the Atlanta area to menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Union Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and George H. Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army. Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unknown destination, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic Ocean at Savannah, Georgia in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the March. Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south, increasing the pressure on Lee's army. Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. Union forces won a decisive victory at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The Confederate capital fell to the Union XXV Corps, composed of black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west and after a defeat at Sayler's Creek, it became clear to Robert E. Lee that continued fighting against the United States was both tactically and logistically impossible. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. In an untraditional gesture and as a sign of Grant's respect and anticipation of folding the Confederacy back into the Union with dignity and peace, Lee was permitted to keep his officer's saber and his horse, Traveller. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman on April 26, 1865, in Durham, North Carolina. On June 23, 1865, at Fort Towson in the Choctaw Nations' area of the Oklahoma Territory, Stand Watie signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives, becoming the last Confederate general in the field to stand down. The last Confederate naval force to surrender was the CSS Shenandoah on November 4, 1865, in Liverpool, England. Entry into the war by Britain and France on behalf of the Confederacy would have greatly increased the South's chances of winning independence from the Union. The Union, under Lincoln and Secretary of State William Henry Seward worked to block this, and threatened war if any country officially recognized the existence of the Confederate States of America (none ever did). In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war in order to get cotton. Cotton diplomacy proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860–62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as US grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half. When the UK did face a cotton shortage, it was temporary, being replaced by increased cultivation in Egypt and India. Meanwhile, the war created employment for arms makers, iron workers, and British ships to transport weapons. Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept as minister to Britain for the Union, and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the Union's blockade. The Confederacy purchased several warships from commercial ship builders in Britain. The most famous, the CSS Alabama, did considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain. War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the Trent Affair, involving the Union boarding of a British mail steamer to seize two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington were able to smooth over the problem after Lincoln released the two. In 1862, the British considered mediation—though even such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. Lord Palmerston reportedly read Uncle Tom’s Cabin three times when deciding on this. The Union victory in the Battle of Antietam caused them to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation further reinforced the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. Despite sympathy for the Confederacy, France's own seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred them from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris. Since the war's end, whether the South could have really won the war has been debated. A significant number of scholars believe that the Union held an insurmountable advantage over the Confederacy in terms of industrial strength and population. Confederate actions, they argue, could only delay defeat. This view is part of the Lost Cause historiography of the war. Southern historian Shelby Foote expressed this view succinctly in Ken Burns's television series on the Civil War: "I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back.… If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don't think the South ever had a chance to win that War." The Confederacy sought to win independence by out-lasting Lincoln. However, after Atlanta fell and Lincoln defeated McClellan in the election of 1864, the hope for a political victory for the South ended. At that point, Lincoln had succeeded in getting the support of the border states, War Democrats, emancipated slaves and Britain and France. By defeating the Democrats and McClellan, he also defeated the Copperheads and their peace platform. Lincoln had also found military leaders like Grant and Sherman who would press the Union's numerical advantage in battle over the Confederate Armies. Generals who did not shy from bloodshed won the war, and from the end of 1864 onward there was no hope for the South. On the other hand, James McPherson has argued that the North’s advantage in population and resources made Northern victory possible, but not inevitable. The American War of Independence and the Vietnam War are examples of wars won by the side with fewer numbers. Confederates did not need to invade and hold enemy territory in order to win, but only needed to fight a defensive war to convince the North that the cost of winning was too high. The North needed to conquer and hold vast stretches of enemy territory and defeat Confederate armies in order to win. Also important were Lincoln's eloquence in rationalizing the national purpose and his skill in keeping the border states committed to the Union cause. Although Lincoln's approach to emancipation was slow, the Emancipation Proclamation was an effective use of the President's war powers. The more industrialized economy of the North aided in the production of arms, munitions and supplies, as well as finances, and transportation. The table shows the relative advantage of the Union over the Confederate States of America (CSA) at the start of the war. The advantages widened rapidly during the war, as the Northern economy grew, and Confederate territory shrank and its economy weakened. The Union population was 22 million and the South 9 million in 1861; the Southern population included more than 3.5 million slaves and about 5.5 million whites, thus leaving the South's white population outnumbered by a ratio of more than four to one compared with that of the North. The disparity grew as the Union controlled more and more southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy. The Union at the start controlled over 80% of the shipyards, steamships, river boats, and the Navy. It augmented these by a massive shipbuilding program. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire southern coastline. Excellent railroad links between Union cities allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South which was unable to augment its much smaller rail system, repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance. The failure of Davis to maintain positive and productive relationships with state governors (especially governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia and governor Zebulon Vance of North Carolina) damaged his ability to draw on regional resources. The Confederacy's "King Cotton" misperception of the world economy led to bad diplomacy, such as the refusal to ship cotton before the blockade started. The Emancipation Proclamation enabled African-Americans, both free blacks and escaped slaves, to join the Union Army. About 190,000 volunteered, further enhancing the numerical advantage the Union armies enjoyed over the Confederates, who did not dare emulate the equivalent manpower source for fear of fundamentally undermining the legitimacy of slavery. Emancipated slaves fought in several key battles in the last two years of the war. European immigrants joined the Union Army in large numbers too. 23.4% of all Union soldiers were German-Americans; about 216,000 were born in Germany. Northern leaders agreed that victory would require more than the end of fighting. It had to encompass the two war goals: Secession had to be totally repudiated, and all forms of slavery had to be eliminated. They disagreed sharply on the criteria for these goals. They also disagreed on the degree of federal control that should be imposed on the South, and the process by which Southern states should be reintegrated into the Union. Reconstruction, which began early in the war and ended in 1877, involved a complex and rapidly changing series of federal and state policies. The long-term result came in the three "Civil War" amendments to the Constitution: the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment, which extended federal legal protections equally to citizens regardless of race; and the Fifteenth Amendment, which abolished racial restrictions on voting. Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer SPECIAL REQUEST FOR TCD FANS: The San Francisco Chronicle is pondering the addition of new cartoons for their paper - a process that seems to be initiated by Darren Bell, creator of Candorville (one of my daily reads - highly recommended). You can read the Chronicle article here and please add your thoughts to the comments if you wish. If anything, put in a good word for Darren and Candorville. I am submitting Town Called Dobson to the paper for their consideration. They seem to have given great weight to receiving 200 messages considering Candorville. I am asking TCD fans to try to surpass that amount. (I get more than that many hate mails a day, surely fans can do better?) This is not a race between Darren and I, it is a hope that more progressive strips can be represented in the printed press of America. So if you read the San Francisco Chronicle or live in the Bay Area (Google Analytics tell me there are a lot of you), please send your kind comments (or naked, straining outrage) to David Wiegand at his published addresses below. If you are a subscriber, cut out your mailing label and staple it to a TCD strip and include it in your letter. candorcomment@sfchronicle.com or David Wiegand Executive Datebook Editor The San Francisco Chronicle 901 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 |

Tuesday, April 29, 2008

Black History: Sing your way to a Contraband Camp

click to enlarge In 1861, Lincoln expressed the fear that premature attempts at emancipation would mean the loss of the border states, and that "to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game." At first, Lincoln reversed attempts at emancipation by Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Generals John C. Fremont (in Missouri) and David Hunter (in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida) in order to keep the loyalty of the border states and the War Democrats. Lincoln mentioned his Emancipation Proclamation to members of his cabinet on July 21, 1862. Secretary of State William H. Seward told Lincoln to wait for a victory before issuing the proclamation, as to do otherwise would seem like "our last shriek on the retreat". In September 1862 the Battle of Antietam provided this opportunity, and the subsequent War Governors' Conference added support for the proclamation. Lincoln had already published a letter encouraging the border states especially to accept emancipation as necessary to save the Union. Lincoln later said that slavery was "somehow the cause of the war". Lincoln issued his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, and said that a final proclamation would be issued if his gradual plan based on compensated emancipation and voluntary colonization was rejected. Only the District of Columbia accepted Lincoln's gradual plan, and Lincoln issued his final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. In his letter to Hodges, Lincoln explained his belief that "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong … And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling ... I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me." Since the Emancipation Proclamation was based on the President's war powers, it only included territory held by Confederates at the time. However, the Proclamation became a symbol of the Union's growing commitment to add emancipation to the Union's definition of liberty. Lincoln also played a leading role in getting Congress to vote for the Thirteenth Amendment, which made emancipation universal and permanent. Confederates enslaved captured black Union soldiers, and black soldiers especially were shot when trying to surrender at the Fort Pillow Massacre. This led to a breakdown of the prisoner exchange program, and the growth of prison camps such as Andersonville prison in Georgia where almost 13,000 Union prisoners of war died of starvation and disease. In spite of the South's shortage of manpower, until 1865, most Southern leaders opposed arming slaves as soldiers. They used them as laborers to support the war effort. As Howell Cobb said, "If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong." Confederate generals Patrick Cleburne and Robert E. Lee argued in favor of arming blacks late in the war, and Jefferson Davis was eventually persuaded to support plans for arming slaves to avoid military defeat. The Confederacy surrendered at Appomattox before this plan could be implemented. A few Confederates discussed arming slaves since the early stages of the war, and some free blacks had even offered to fight for the South. In 1862 Georgian Congressman Warren Akin supported the enrolling of slaves with the promise of emancipation, as did the Alabama legislature. Support for doing so also grew in other Southern states. A few all black Confederate militia units, most notably the 1st Louisiana Native Guard, were formed in Louisiana at the start of the war, but were disbanded in 1862. In early March, 1865, Virginia endorsed a bill to enlist black soldiers, and on March 13 the Confederate Congress did the same. The Emancipation Proclamation greatly reduced the Confederacy's hope of getting aid from Britain or France. Lincoln's moderate approach succeeded in getting border states, War Democrats and emancipated slaves fighting on the same side for the Union. The Union-controlled border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. All abolished slavery on their own, except Kentucky and Delaware. The great majority of the 4 million slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, as Union armies moved South. The 13th amendment, ratified December 6, 1865, finally freed the remaining slaves in Kentucky, Delaware, and New Jersey, that numbered 225,000 for Kentucky, 1,800 in Delaware, and 18 in New Jersey as of 1860. At Fort Monroe in southeastern Virginia, Brigadier General Benjamin Butler, commander, came into the custody of three slaves who had made their way across Hampton Roads from Confederate-occupied Norfolk County, Virginia and presented themselves at Union-held Fort Monroe. General Butler refused to return escaped slaves to masters supporting the Confederacy, which amounted to classifying them as "contraband," although credit for first use of that terminology occurred elsewhere. Three slaves, Frank Baker, James Townsend and Sheppard Mallory had been contracted by their owners to the Confederate Army to help construct defense batteries at Sewell's Point across the mouth of Hampton Roads from Union-held Fort Monroe. They escaped at night and rowed a skiff to Old Point Comfort, where they sought asylum at the adjacent Fort Monroe. Prior to the War, the owners of the slaves would have been legally entitled to request their return (as property) and this would have in all likelihood have occurred. However, Virginia had just declared (by secession) that it no longer considered itself part of the United States. General Butler, who was educated as an attorney, took the position that, if Virginia considered itself a foreign power to the U.S., then he was under no obligation to return the 3 men; he would instead hold them as "contraband of war." Thus, when Confederate Major John B. Cary made the request for their return as Butler had anticipated, it was denied on the above basis. While not truly free men (yet), the three men undoubtedly were much satisfied to have their new status as "contraband" rather than slaves. Gen. Butler paid the escaped slaves nothing, and kept them as slaves, as he so termed them. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells issued a directive, September 25, 1861 which gave "persons of color, commonly known as contrabands," in the employment of the Union Navy pay at the rate of $10 and a full day's ration. It was not until three weeks later the Union Army followed suit, paying male 'contrabands' $8 a month and females $4, at Fort Monroe, and only specific to that command. The Confiscation Act of 1861 declared that August that any property used by the Confederate military, including slaves, could be confiscated by Union forces. The next March, the Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves forbade the restoring of such human seizures. The word spread quickly among southeastern Virginia's slave communities. While becoming a "contraband" did not mean full freedom, it was apparently seen by many slaves as at least a step in that direction. The day after Butler's decision, many more escaped slaves also found their way to Fort Monroe appealing to become contraband. As the number of former slaves grew too large to be housed inside the Fort, from the burned ruins of the City of Hampton the Confederates had left behind, the contrabands erected housing outside the crowded base. They called their new settlement Grand Contraband Camp (which they nicknamed "Slabtown"). By the end of the war in April 1865, less than 4 years later, an estimated 10,000 had applied to gain "contraband" status, many living nearby. Near Fort Monroe, but outside its protective walls in Elizabeth City County, in an area which later became part of the campus of Hampton University, both adult and child contrabands were taught to read and write by pioneering teacher Mrs. Mary S. Peake and others. Defying a Virginia law against educating slaves, classes were held outdoors under a certain large oak tree. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation was read to the contrabands and free blacks there, giving the tree its name and claim to fame as the Emancipation Oak. However, due to some political considerations when drafting the Proclamation, for most of the contrabands, true emancipation did not come until the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishing slavery was ratified in late 1865. In modern times, the Contraband Historical Society was organized by their descendants, to honor and perpetuate their story. Authors such as Phyllis Haislip have written about the plight of contraband slaves as well. Enslaved African Americans did not wait for Lincoln's action before escaping and seeking freedom behind Union lines. From early years of the war, hundreds of thousands of African Americans escaped to Union lines, especially in occupied areas like Norfolk and the Hampton Roads region in 1862, Tennessee from 1862 on, the line of Sherman's march, etc. So many African Americans fled to Union lines that commanders created camps (called contraband camps) and schools for them, where both adults and children learned to read and write. The American Missionary Association entered the war effort by sending teachers south to such contraband camps, for instance establishing schools in Norfolk and on nearby plantations. In addition, nearly 200,000 African-American men served with distinction as soldiers and sailors with Union troops. Most of those were escaped slaves. Once the slaves felt free, they began to sing spirituals as the walked the long distances up the Underground Railroad or to the Union controlled contraband camps. The term spiritual is derived from spiritual song. The King James Bible's translation of Ephesians V.19 is: "Speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord." Negro spiritual first appears in print in the 1860's, where slaves are described as using the noun "spiritual"for religious songs sung sitting or standing in place, and spiritual shouts for more dance-like music. Although numerous rhythmically and sonic elements of spirituals can be traced to African sources, nonetheless it is a fact that spirituals are a musical form that is indigenous and specific to the religious experience in the United States of Africans transported from Africa. They are a result of the interaction of African religious elements with music and religion derived from Europe. Further, this interaction occurred only in the United States. Africans converted to Christianity in other parts of the world, even in the Caribbean and Latin American, did not evolve this form. Negro spirituals were primarily expressions of religious faith. They may also have served as socio-political protests veiled as assimilation to white American culture. They were originated by enslaved African-Americans in the United States. Slavery was introduced to the British colonies in the early seventeenth century, and enslaved people largely replaced indentured servants as an economic labor force during the 17th century. These people would remain in bondage for the entire 18th century and much of the 19th century. Most were not fully emancipated until the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. During slavery in the United States, there were systematic efforts to de-Africanize the captive Black workforce. Enslaved people were forbidden from speaking their native languages. Restrictions were placed on the religious expression of slaves. Rows of benches in places of worship discouraged congregants from spontaneously jumping to their feet and dancing. The use of musical instruments of any kind often was forbidden, and slaves were ordered to desist from the "paganism" of the practice of spiritual possession. Nonetheless, the Christian principles that teach those who suffer on earth hold a special place with God in heaven undoubtedly spoke to the enslaved who saw this as hope and could certainly relate to the suffering of Jesus. For this reason many slaves genuinely embraced Christianity. Because they were unable to express themselves freely in ways that were spiritually meaningful to them, enslaved Africans often held secret religious services. During these “bush meetings,” worshippers were free to engage in African religious rituals such as spiritual possession, speaking in tongues and shuffling in counterclockwise ring shouts to communal shouts and chants. It was there also that enslaved Africans further crafted the impromptu musical expression of field songs into the so-called "line singing" and intricate, multi-part harmonies of struggle and overcoming, faith, forbearance and hope that have come to be known as "Black Spirituals." While slaveowners used Christianity to teach enslaved Africans to be long-suffering, forgiving and obedient to their masters, as practiced by the enslaved, it became something of a liberation theology. The story of Moses and The Exodus of the "children of Israel" and the idea of an Old Testament God who struck down the enemies of His "chosen people" resonated deeply with the enslaved ("He's a battleaxe in time of war and a shelter in a time of storm"). In Black hands and hearts, Christian theology became an instrument of liberation. So, too, in many instances did the spirituals themselves. Spirituals sometimes provided comfort and eased the boredom of daily tasks, but above all, they were an expression of spiritual devotion and a yearning for freedom from bondage. Songs like "Steal Away (to Jesus)", or "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" raised unexpectedly in a dusty field, or sung softly in the dark of night, signaled that the coast was clear and the time to escape had come. The River Jordan became the Ohio River, or the Mississippi, or another body of water that had to be crossed on the journey to freedom. “Wade in the Water” contained explicit instructions to fugitive slaves on how to avoid capture and the route to take to successfully make their way to freedom. Leaving dry land and taking to the water was a common strategy to throw pursuing bloodhounds off one's trail. “The Gospel Train”, and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” all contained veiled references to the Underground Railroad, and Follow the Drinking Gourd contained a coded map to the Underground Railroad. The title itself was an Africanized reference to the Big Dipper, which pointed the way to the North Star and freedom in Canada. In the 1850s, Reverend Alexander Reid, superintendent of the Spencer Academy in the old Choctaw Nation, hired some enslaved Africans from the Indians for some work around the school. He heard two of them, "Uncle Wallace" and "Aunt Minerva" Willis, singing religious songs they had composed. Among these songs were Swing Low, Sweet Chariot, Steal Away to Jesus, The Angels are Coming, I'm a Rolling, and Roll Jordan Roll. Later, Reid, who left Indian Territory at the beginning of the Civil War, attended a musical program put on by a group of Negro singers from Fisk University. Although they were singing mostly popular music of the day, Reid thought the songs he remembered from his time in the Choctaw Nation would be appropriate. He and his wife transcribed the songs of the Willises as they remembered them and sent them to Fisk University. The Jubilee Singers put on their first performance singing the old captives' songs at a religious conference in 1871. The songs were first published in 1872 in a book titled Jubilee Songs as Sung by the Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, by Thomas F. Steward. Later these religious songs became known as "Black spirituals" to distinguish this music from the spiritual music of other peoples. Wallace Willis died in 1883 or 84. Over time the pieces the Jubilee Singers performed came to be arranged and performed by trained musicians. In 1873, Mark Twain, whose father had owned slaves, found Fisk singing to be "in the genuine old way" he remembered from childhood, but an 1881 performance review said that "they have lost the wild rhythms, the barbarity, the passion." Fifty years on, Zora Neale Hurston in her 1938 book The Sanctified Church criticized Fisk singers, and similar groups at Tuskegee and Hampton, as using a "Glee Club style" that was "full of musicians' tricks" not to be found in the original spirituals, urging readers to visit an "unfashionable Negro church" to experience real spirituals. A second important early collection of lyrics is Slave Songs of the United States by William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison (1867). A group of lyrics to "Negro spirituals" was published by Col. Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who served as the commander of a regiment of former slaves in the Civil War, in an article in The Atlantic Monthly and subsequently included in his 1869 memoir Army Life in a Black Regiment (1869). Musicologist George Pullen Jackson extended the term to a wider range of folk hymnody, as in his 1938 book White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands, but this does not appear to have been widespread usage previously. "Spiritual song" was often used in the white Christian community through the 19th century (and indeed much earlier), but not "spiritual." But those slaves who didn't escape to a contraband camp or via the Underground Railroad, were still considered as property by the Confederate States. The spirituals offered them no solace. Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer SPECIAL REQUEST FOR TCD FANS: The San Francisco Chronicle is pondering the addition of new cartoons for their paper - a process that seems to be initiated by Darren Bell, creator of Candorville (one of my daily reads - highly recommended). You can read the Chronicle article here and please add your thoughts to the comments if you wish. If anything, put in a good word for Darren and Candorville. I am submitting Town Called Dobson to the paper for their consideration. They seem to have given great weight to receiving 200 messages considering Candorville. I am asking TCD fans to try to surpass that amount. (I get more than that many hate mails a day, surely fans can do better?) This is not a race between Darren and I, it is a hope that more progressive strips can be represented in the printed press of America. So if you read the San Francisco Chronicle or live in the Bay Area (Google Analytics tell me there are a lot of you), please send your kind comments (or naked, straining outrage) to David Wiegand at his published addresses below. If you are a subscriber, cut out your mailing label and staple it to a TCD strip and include it in your letter. candorcomment@sfchronicle.com or David Wiegand Executive Datebook Editor The San Francisco Chronicle 901 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 |

Posted by

Storm Bear

at

11:32 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cartoons, civil war, comics, contraband camps, negro spirituals, slavery, webcomics

You Are What You Wear

XKCD: |

Monday, April 28, 2008

Black History: First Shots of the Civil War

click to enlarge Several forts had been constructed in the harbor, including Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie. Fort Moultrie was the oldest and was the headquarters of the garrison. However, it had been designed essentially as a gun platform for defending the harbor, and its defenses against land-based attacks were feeble; during the crisis, the Charleston newspapers commented that sand dunes had grown up against the walls in such a way that the wall could easily be scaled. When the garrison began clearing away the dunes, the papers objected. Fort Sumter, by contrast, dominated the entrance to Charleston Harbor and was thought to be one of the strongest fortresses in the world once its construction was completed; in the autumn of 1860 work was nearly done, but the fortress was thus far garrisoned by a single soldier, who functioned as a lighthouse keeper. However, it was considerably stronger than Fort Moultrie, and its location on a sandbar prevented the sort of land assault to which Fort Moultrie was so vulnerable. Under the cover of darkness on December 26, 1860, Anderson spiked the cannons at Fort Moultrie and moved his command to Fort Sumter. South Carolina authorities considered this a breach of faith and demanded that the fort be evacuated. At that time President James Buchanan was still in office, pending Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, 1861. Buchanan refused their demand and mounted a relief expedition in January 1861, but shore batteries fired on and repulsed the unarmed merchant ship, Star of the West. The battery that fired was manned by cadets from The Citadel, who were the only trained artillerists in the service of South Carolina at the time. Following the formation of the Confederacy in early February, there was some internal debate among the secessionists as to whether the capture of the fort was rightly a matter for the State of South Carolina or the newly declared national government in Montgomery, Alabama. South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens was among the states' rights advocates who felt that all of the property in Charleston harbor had reverted to South Carolina upon that state's secession as an independent commonwealth. This debate ran alongside another discussion as to how aggressively the properties—including Forts Sumter and Pickens—should be obtained. Jefferson Davis, like his counterpart in Washington, D.C., preferred that his side not be seen as the aggressor. Both sides believed that the first side to use force would lose precious political support in the border states, whose allegiance was undetermined; prior to Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, five states had voted against secession, including Virginia, and Lincoln openly offered to evacuate Fort Sumter if it would guarantee Virginia's loyalty. In March, Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard took command of South Carolina forces in Charleston; on March 1, Davis had appointed him the first general officer in the armed forces of the new Confederacy, specifically to take command of the siege. Beauregard made repeated demands that the Union force either surrender or withdraw and took steps to ensure that no supplies from the city were available to the defenders, whose food was running out. He also increased drills amongst the South Carolina militia, training them to operate the guns they manned. Ironically enough, Anderson had been Beauregard's artillery instructor at West Point; the two had been especially close, and Beauregard had become Anderson's assistant after graduation. Both sides spent the month of March drilling and improving their fortifications to the best of their abilities. By April 4, President Lincoln, discovering that supplies in the fort were shorter than he had previously known, and believing a relief expedition to be feasible, ordered merchant vessels escorted by the United States Navy to Charleston. On April 6, 1861, Lincoln notified South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens that "an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions only, and that if such attempt be not resisted, no effort to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, [except] in case of an attack on the fort." In response, the Confederate cabinet, meeting in Montgomery, decided on April 9 to open fire on Fort Sumter in an attempt to force its surrender before the relief fleet arrived. Only Secretary of State Robert Toombs opposed this decision: he reportedly told Jefferson Davis the attack "will lose us every friend at the North. You will wantonly strike a hornet's nest. ... Legions now quiet will swarm out and sting us to death. It is unnecessary. It puts us in the wrong. It is fatal." The Confederate Secretary of War telegraphed Beauregard that if he were certain that the fort was to be supplied by force, "You will at once demand its evacuation, and if this is refused proceed, in such a manner as you may determine, to reduce it." Beauregard dispatched aides to Fort Sumter on April 11 and issued their ultimatum. Anderson refused, though he reportedly commented, "Gentlemen, if you do not batter the fort to pieces about us, we shall be starved out in a few days." Further discussions after midnight proved futile. At 3:20 a.m., April 12, 1861, the Confederates informed Anderson that they would open fire in one hour. At 4:30 a.m., a single mortar round fired from Fort Johnson exploded over Fort Sumter, signaling the start of the bombardment from 43 guns and mortars at Fort Moultrie, Fort Johnson, and Cummings Point. Edmund Ruffin, a notable secessionist, had traveled to Charleston in order to be present for the beginning of the war, and was present to fire the first shot at Sumter after the signal round. Anderson withheld his fire until 7:00 a.m., when Capt. Abner Doubleday fired a shot at the Ironclad Battery at Cummings Point. But there was little Anderson could do with his 60 guns; he deliberately avoided using guns that were situated in the fort where casualties were likely. Unfortunately, the fort's best cannons were mounted on the uppermost of its three tiers, where his troops were most exposed to enemy fire. The fort had been designed to hold out against a naval assault, and naval warships of the time did not mount guns capable of elevating to fire over the walls of the fort; however, the land-based cannons manned by the South Carolina militia were capable of landing such indirect fire on Fort Sumter. Fort Sumter's garrison could only safely fire the guns on the lower levels, which themselves, by virtue of being in stone emplacements, were largely incapable of indirect fire that could seriously threaten Fort Moultrie. Moreover, although the Federals had moved as much of their supplies to Fort Sumter as they could manage, the fort was quite low on ammunition, and was nearly out at the end of the 34-hour bombardment. The shelling of Fort Sumter from the batteries ringing the harbor awakened Charleston's residents (including diarist Mary Chesnut), who rushed out into the predawn darkness to watch the shells arc over the water and burst inside the fort. The bombardment lasted through the night until the next morning, when a shell hit the officers' quarters, starting a serious fire that threatened the main powder magazine. The fort's central flagpole also fell. During the period the flag was down, before the garrison could improvise a replacement, several Confederate envoys arrived to inquire whether the flag had been lowered in surrender. Anderson agreed to a truce at 2:00 p.m., April 13, 1861. Terms for the garrison's withdrawal were settled by that evening and the Union garrison surrendered the fort to Confederate personnel at 2:30 p.m., April 14. The soldiers were safely transported back to Union territory by the U.S. Navy squadron whose anticipated arrival as a relief fleet had prompted the barrage. No one from either side was killed during the bombardment, with only five Union and four Confederate soldiers severely injured. During the 100-gun salute to the U.S. flag—Anderson's one condition for withdrawal—a pile of cartridges blew up from a spark, killing one soldier (Private Daniel Hough) and seriously injuring the rest of the gun crew, one mortally (Private Edward Galloway); these were the first fatalities of the war. The salute was stopped at fifty shots. Anderson lowered the Fort Sumter Flag and took it with him to the North, where it became a widely known symbol of the battle, and a rallying point for supporters of the Union. The bombardment of Fort Sumter was the first military action of the American Civil War. Following the surrender, Northerners rallied behind Lincoln's call for all of the states to send troops to recapture the forts and to preserve the Union. With the scale of the rebellion apparently small so far, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers for 90 days. For months before that, several Northern governors had discreetly readied their state militias; they began to move forces the next day. The ensuing war lasted four years, effectively ending in April 1865, with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Charleston Harbor was completely in Confederate hands for the four-year duration of the war, a hole in the Union naval blockade. Union forces retook the fort just days after Lee's surrender and the collapse of the Confederacy. On April 14, 1865, four years to the day after lowering the Fort Sumter Flag in surrender, Anderson (by then a major general, although ill and in retired status) raised it over the fort again. Two of the cannons used at Fort Sumter were later presented to Louisiana State University by General William Tecumseh Sherman, who was president of the university before the war began. Birth Of A Notion Disclaimer SPECIAL REQUEST FOR TCD FANS: The San Francisco Chronicle is pondering the addition of new cartoons for their paper - a process that seems to be initiated by Darren Bell, creator of Candorville (one of my daily reads - highly recommended). You can read the Chronicle article here and please add your thoughts to the comments if you wish. If anything, put in a good word for Darren and Candorville. I am submitting Town Called Dobson to the paper for their consideration. They seem to have given great weight to receiving 200 messages considering Candorville. I am asking TCD fans to try to surpass that amount. (I get more than that many hate mails a day, surely fans can do better?) This is not a race between Darren and I, it is a hope that more progressive strips can be represented in the printed press of America. So if you read the San Francisco Chronicle or live in the Bay Area (Google Analytics tell me there are a lot of you), please send your kind comments (or naked, straining outrage) to David Wiegand at his published addresses below. If you are a subscriber, cut out your mailing label and staple it to a TCD strip and include it in your letter. candorcomment@sfchronicle.com or David Wiegand Executive Datebook Editor The San Francisco Chronicle 901 Mission St. San Francisco, CA 94103 |

Posted by

Storm Bear

at

9:33 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: cartoons, civil war, comics, fort sumter, slavery, south carolina, webcomics

Overdrawn

|

Posted by

Anonymous

at

4:17 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Recession, Tax Rebates, the Second Great Depression

Who Do You Think You Are, Mr. Snipes? Haliburton?

Wesley Snipes Gets 3 Years for Not Filing Tax Returns OCALA, Fla. — A federal judge on Thursday sentenced the actor Wesley Snipes to three years in prison for willfully failing to file tax returns. In the first episode of "Sanford and Son", I remember a scene where Fred was arguing with his son about driving out at night to visit some friends who lived in a white neighborhood. "Check your lights, son. The cops are hell on a nigger with no lights." So imagine what they'll do to a brother who doesn't pay his taxes. It's easier fighting vampires than the IRS. |