Appearing at The Blogging Curmudgeon, My Left Wing, and the Independent Bloggers' Alliance.  I could feel a huge concussion wave, and then I couldn’t hear anything. I told my sergeants my ears were hurting and that I felt really weird. My vision was acting all strange. -- Spc. Paul Thurman Paul Thurman was not supposed to be deployed. His brain had been damaged before he even left Ft. Bragg; a training accident in which a log was dropped on his head. Brain scans showed evidence of lesions. Yet, inexplicably, he was sent to Iraq. There he sustained a second head trauma; another training accident. An IED simulator went off three feet from his head. Soon he was having dizzy spells, was losing his balance and couldn’t sleep. But Thurman's Kafkaesque journey through the Army system continues. Instead of proper treatment, he has received disciplinary actions for problems resulting from his injury; an Article 15 for leaving a formation to take anti-seizure medication and a bad counseling statement for refusing to attend an 80 hour driving course. His medical file says he cannot drive. Today he is hoping for a court martial hearing so that his story can heard farther up the chain of command. Brain trauma is the signature injury of the Iraq war. As increasingly elaborate body armour protects the torso, and even the limbs, the brain is still vulnerable to shock waves that helmets cannot deter. For the first time, the U.S. military is treating more head injuries than chest or abdominal wounds, and it is ill-equipped to do so. According to a July 2005 estimate from Walter Reed Army Medical Center, two-thirds of all soldiers wounded in Iraq who don't immediately return to duty have traumatic brain injuries. Referred to as "the silent injury," in many cases the damage caused by concussive waves is not immediately apparent. And these "closed-head" injuries are harder to treat than even those commonly suffered by motorcyclists. Traumatic brain injuries from Iraq are different, said P. Steven Macedo, a neurologist and former doctor at the Veterans Administration. Concussions from motorcycle accidents injure the brain by stretching or tearing it, he said. But in Iraq, something else is going on. Indeed it appears that even those troops who are not at close proximity to IED blasts can be affected. It is estimated that one third of our combatants may be suffering brain injuries, many who don't even know that damage has occurred. This has prompted the VA to start screening all Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who enroll. That will still leave roughly two thirds unexamined, as most never apply for veteran's health benefits. More tragic, the Pentagon has demonstrated far less vigilance than the VA in addressing these pernicious injuries. What's baffling is the Pentagon's failure to work with Congress to provide a steady stream of funding for research on traumatic brain injuries. Meanwhile, the high-profile firings of top commanders at Walter Reed have shed light on the woefully inadequate treatment for troops. In these circumstances, soldiers face a struggle to get the long-term rehabilitation necessary for treatment of a traumatic brain injury. At Walter Reed, Macedo said, doctors have chosen to medicate most brain-injured patients, even though cognitive rehabilitation, including brain teasers and memory exercises, seems to hold the most promise for dealing with the disorder. In fact, last summer the Pentagon reacted to the startling numbers of brain injuries by cutting it's funding request for treatment and research of the problem in half; from $14 million to $7 million. That maneuver seems consistent with a larger agenda of minimizing treatment funds to troops across the board. As reported by NPR, troop disabilities are being pencil-whipped down to nothing. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Parker USA (Ret.) found that the Pentagon is now providing disability payments to fewer veterans than they were before the war. Parker started digging through Pentagon data, and the numbers he found shocked him. He learned that the Pentagon is giving fewer veterans disability benefits today than it was before the Iraq war — despite the fact that thousands of soldiers are leaving the military with serious injuries. One of the Pentagon's disappearing tricks is assigning injured veterans drastically lower disability ratings than their injuries demand. Tim Ngo who suffered a traumatic brain injury was rated by the Pentagon as only 10 per cent disabled. Tim Ngo almost died in a grenade attack in Iraq. He sustained a serious head injury; surgeons had to cut out part of his skull. At Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., he learned to walk and talk again. Even a 30 per cent rating would have guaranteed him a monthly check and enrollment in the military's health-care system. As it was he was given a medical discharge and a small severance payment; leaving him adrift, with no coverage, until he had matriculated into the VA system. Instead, Ngo enrolled with the Department of Veterans Affairs. Typically, there's a waiting period for the VA. Since then, Ngo's injuries have been acknowledged by the VA as so serious that he has been granted 100 per cent disability. In fact, more than half of disabled veterans who transfer into the VA system have their disabilities uprated from 10-20 per cent to over 30 per cent. The Senate is currently investigating concerns that the DOD is simply punting their disabled veterans to the VA to improve their own bottom line. What we have is a military system near the breaking point. Our troop levels are stretched so thin that we are redeploying injured, even broken, troops, and a chronically underfunded VA is left to clean up the damage. Ironically, the very resources that are keeping more of our troops alive on the battlefield, are returning them to a living hell of inadequate treatment. These are the war's injured who once would have been the war's dead. And it is the unexpected number of casualties who in a previous medical era would have been fatalities that has sunk the outpatient clinics at Walter Reed and left those in the VA system lost and adrift. So we are bringing back more of our troops alive but to what kind of life? Marine Lance Cpl. Brian Vargas was a high school football player. Now, even though he looks fit, he cannot toss the football with his buddies, let alone be part of pickup games with other off-duty Marines. |

Sunday, April 22, 2007

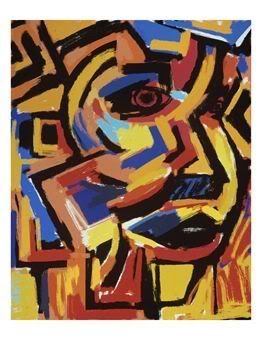

This Is Your Brain On Iraq

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment